Search for articles, topics or more

browse by topics

Search for articles, topics or more

M Magazine catches up with Fukasawa to discuss how his philosophy plays out in these new pieces and how his approach to design has shifted and refined over his career.

Naoto Fukasawa has designed everything from watches, CD players and eyewear to pens, chairs and his L-shaped house and studio. Over his career he has worked for a host of international brands, written several books and held roles as an educator, curator, advisor and more. Across all of these endeavours, he applies his nuanced and gentle design philosophy, which is based on the belief that design is most successful when it is so user-friendly that you may not even notice it. Fukasawa enacts this philosophy by paying close attention to details, with a deep understanding of how objects, people and places interact with each other. Recently, he has turned his careful attention to the design of a chaise longue (called Tuscany) and an armchair (called Cinnamon) for Molteni&C.

Cinnamon | Design Naoto Fukasawa

Cinnamon | Design Naoto Fukasawa

Cinnamon | Design Naoto Fukasawa

Cinnamon | Design Naoto Fukasawa

Most people know you predominantly as a furniture designer, but a lot of your early work was in consumer electronics. How has working in that field influenced your broader practice?

I started out as an industrial designer. I was interested in the forms and shapes of every kind of object, whether that be furniture or electronic devices. After school, I joined a watch company. At that time, watches were more focused on craft and micro-electronics, but they were changing to incorporate IT and micro-technology, so I was lucky enough to learn about designing for new technologies like LCD watches, digital watches, micro-printers or small projectors.

Then I worked in other roles around the world and began talking to other designers about how to design mass-produced electronic objects when their form isn’t defined by their use. Can we treat these objects like sculptures? It was an interesting time for me, because I was doubting things and asking myself: “Is this true design?” From there, I became an expert on form and shape. People called me the “Detail King” because I could make anything. I got many awards for new types of technological objects and that was phase one of my career.

What was the next step after that?

After I came back to Japan from California, I witnessed another level of design and became more aware of design in Europe. Lots of offers from the furniture industry began coming in. I don’t know why that happened, because I was mostly interested in making unique proposals for electronics. I think Italian companies saw me as an interesting designer who could build a bridge between the high-tech and furniture industries.

What did you see as the differences between these fields?

I liked that the furniture objects were way higher in quality than those in the IT industry. I don’t like the fact that when a technology changes, the design has to change too. That isn’t interesting for me so I am now more focused on chairs, sofas, dining tables, interior architecture and other physical things that are kept forever.

Something you are well known for is the Supernormal project and philosophy, which you developed in 2006. Does this idea of very well-designed everyday objects still resonate with you?

I believe the Supernormal philosophy never changes. Often, I propose Supernormal designs to clients but they think they want me to make something special. In general, that’s not true, that's only fashion. While fashion can be good, a tool doesn't need to be fancy, it should be normal.

You seem like someone who thinks quite deeply about the brands you work with and how your work will sit in their collection. When you started working on your new pieces with Molteni&C, what were you drawn to within the company?

When Molteni&C first contacted me, I looked carefully at their history. They have worked with some genius designers and architects as well as the archives of well-known designers such as Gio Ponti. Carlo Molteni, President of the Company, is still very involved in product development. I liked that it is a close family business based on craftsmanship.

The chaise longue is a fascinating typology of furniture because you don't see it so often anymore – it feels almost like something from the 20th century. How did you approach designing Tuscany?

There are not many famous chaise longues, only the iconic pieces by the Eames or Le Corbusier. They both have very metallic structures, whereas Molteni&C has a history of using dark wood and less metal, so this one simple material became my starting point.

Another factor is that the chaise longue’s shape is defined by the body: it’s fixed. So I looked for inspiration in the furniture’s environment, I tried to imagine where the chaise longue would be placed – by a beach or poolside, by a mountainside or looking over the rolling hills of Siena in Tuscany. That is a great location to relax and recharge. Our lived environment defines the object so we cannot think of the object itself without looking at the environment.

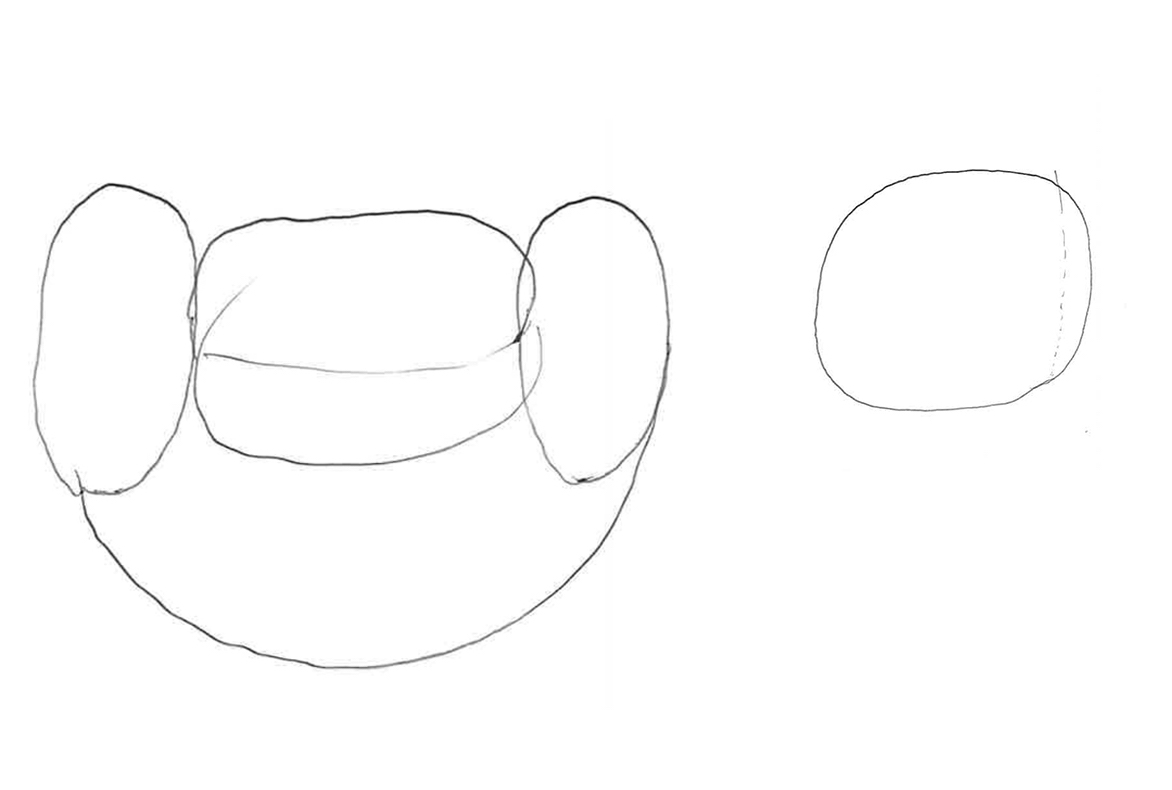

Tuscany Chaise Longue – Paper Prototype

Tuscany Chaise Longue – Paper Prototype

Tuscany Chaise Longue – Paper Prototype

Tuscany Chaise Longue – Paper Prototype

Cinnamon | Design Naoto Fukasawa

Cinnamon | Design Naoto Fukasawa

The design for Cinnamon, your armchair, is a more generous, enveloping form. What did you aim for with that design?

The armchair is a mass of polyurethane. It is like a big stuffed bear. An armchair is like a fat dog or a cute elephant – in other words, a friend that is always around. It has character, it has a soul, and that is very important.

How do you work with clients to develop these ideas?

I think we recently found the right word as a studio to describe this – ad hoc. It is about reacting to what is happening and communicating. We have the kinds of conversations where a client might say, “Oh, that is good” about a project or an object, and I react and we make decisions. We work very quickly.

People sometimes interpret design as an expression of the designer or a statement of their artistry, whereas you've described it as more responsive to a place or person. That seems very distinctive in your work.

Yes, it’s very, very important. Design should be harmonising, making relationships between human beings, environments and objects. When things are well designed, no one really feels it because it’s unconscious, but when an object is uncomfortable everybody notices and cares. It’s often ignored or forgotten because it’s seen as a tiny discomfort but it is so important. Fixing it to be better makes the world a lot better.

Throughout your career, our understanding of how design impacts the planet has gained urgency. Have you noticed a change in the industry or how you approach design in relation to the climate crisis?

Designing and mass-producing results in many things that are bad for the environment but good for the economy. Everybody once focused on constantly making many things, particularly high-quality, expensive things – that was the economic cycle. That cycle is not right anymore. Now, you also have to take into account what the most important thing for sustainability is. We should forget about objects which have a short life, they are no good.

I find “recycle” a funny word and don’t like it much, because of course it is good and we have to use materials that are broken down, but if things are good in the first place, people won’t want to throw them away. I believe, for example, that if I design a chair which no one throws away, that is sustainable because it never dies. “Maintain” is a more important approach for the environment. We shouldn’t forget the importance of people believing in and loving things. It helps those objects have a long life.

Again, it's that emphasis on understanding the relationship between people and objects.

Yes, I worry so much about people forgetting the human touch. There is a focus on the virtual or digital but actually your body interacts with everything, every day. We should not forget about the sensory act – it is a more delicate and more precise way of communicating. What is important, for me, is making a better life and spending a better life.

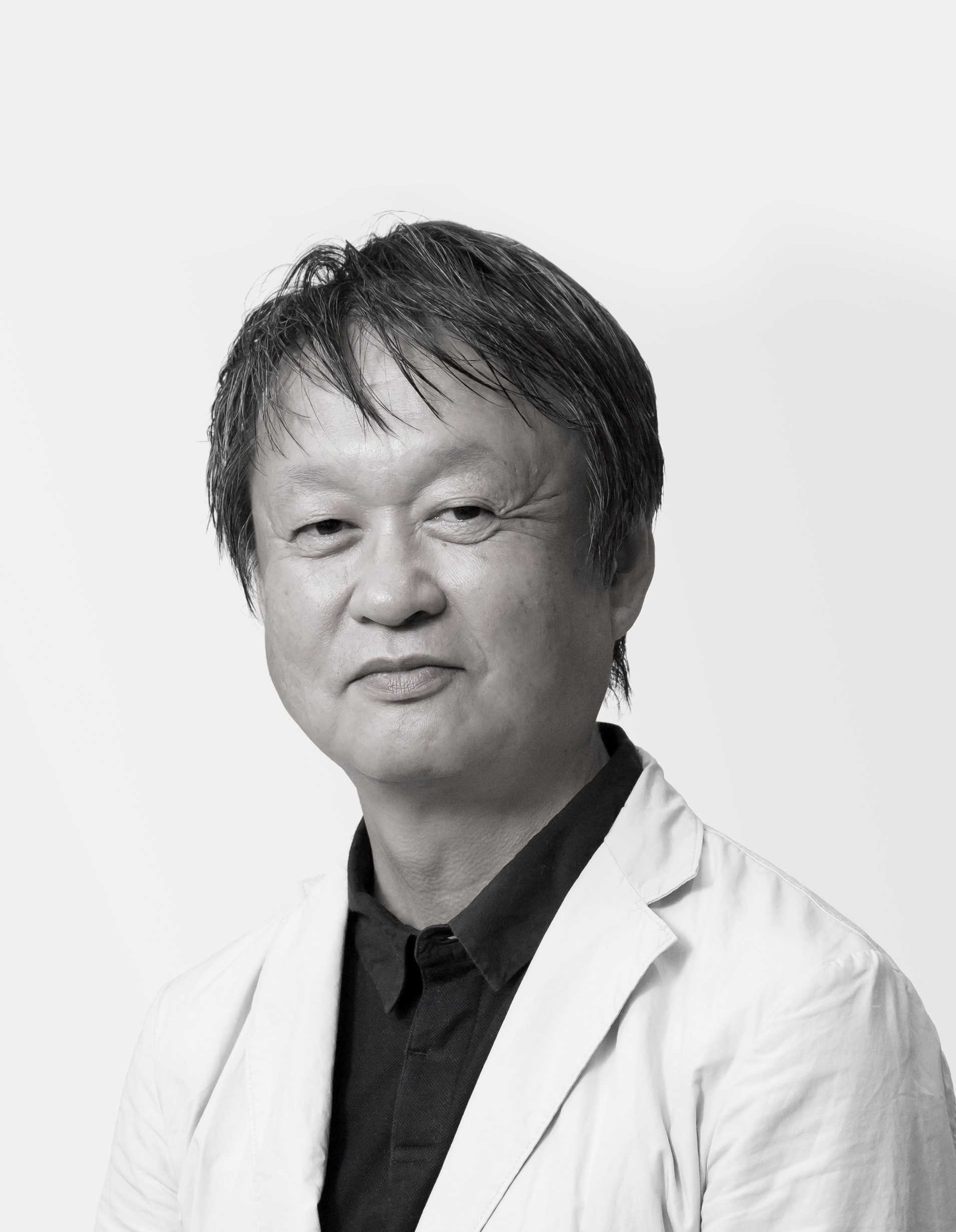

Naoto Fukasawa

Naoto Fukasawa has designed everything from watches, CD players and eyewear to pens, chairs and his L-shaped house and studio. Over his career he has worked for a host of international brands, written several books and held roles as an educator, curator, advisor and more. Across all of these endeavours, he applies his nuanced and gentle design philosophy, which is based on the belief that design is most successful when it is so user-friendly that you may not even notice it. Fukasawa enacts this philosophy by paying close attention to details, with a deep understanding of how objects, people and places interact with each other. Recently, he has turned his careful attention to the design of a chaise longue (called Tuscany) and an armchair (called Cinnamon) for Molteni&C.

The photographer Jeff Burton is known for the cinematic quality of his work: bathers by a hotel pool become a study in saturated colour; tanned bodies are seen at one remove, distorted by mirrored surfaces; a woman’s glance is glimpsed through a car’s rearview mirror.

Lunar New Year is the most important day in China’s lunisolar calendar.

The holidays are a time to eat, drink and make merry – the most convivial time of the year.

Thanks for your registration.